It is part of the human condition to feel compelled to move forward, even when it isn’t clear where forward really is.

Forward motion involves agency: intending something and realizing that intention. Agency takes flight as a narrative, a story about who are we and where we’re going. People get uncomfortable when they don’t have a story about what they want, or aren’t sure the story they’ve been living by is sufficiently compelling.

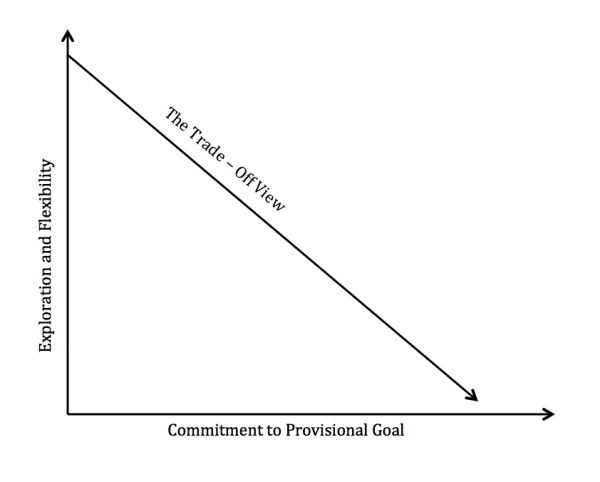

As people work through this discomfort, one of the traps is the wrong (but seductive!) idea that the more one commits to any story, any provisional goal, the less flexibility one has. That picture looks something like the following:

The general result of this “trade-off view” is a combination of listlessly doing the work at hand and aimlessly exploring. This combination can go on for quite some time, generating a sense of disaffection that further reinforces the lack of commitment to whatever provisional goal seems like the leading candidate.

The way out is to embrace provisional goals –– and to have at least two. One provisional goal should be a story that can be pursued right now, a story that feels realistic to take action on more or less each day. And another provisional goal should encompass the exploration that matters most. Call this “living two stories.”

These narratives, embodied in provisional goals, could be about a personal achievement, transforming something in the world, being or becoming a certain way, finding or building something, making a discovery, or any of a range of other pursuits. Part of what’s important about narrative is that it creates a frame for “seeing as”: perceiving the situations we encounter, people we meet, ideas we learn about in terms of their relation to a goal. If I’m on a quest to accelerate a cure for paralysis (Mark Pollock Trust) or unlock the potential of homeless youth who are committed to excellence in creative fields (Reciprocity Foundation), it isn’t hard to see almost everything as a resource, an analogy, a lesson, or something to enable this enterprise. The same goes for less grand goals, like “get enough client interest to become a self-employed interior designer” or “find a good part-time engineering job that enables me to pick up my daughter from school every afternoon without cutting my income by more than a third.”

So, let’s walk through what it might be like for someone to realize their “two stories”. Perhaps she’s a mid-level lawyer, initially drawn into the field through a kind of idealism about law as the mechanism for structuring society, but is now doing corporate transactions, well but without extreme distinction, and feeling a bit trapped by a cushy income and a multitude of commitments. Perhaps her mid-sized firm has been acquired by a larger one, and this transaction has dislocated relationships and brought a sense of heightened anxiety. She feels that something needs to evolve, but she isn’t sure how, or how to pursue that evolution at a time when it seems hard enough simply to stay afloat.

Our lawyer lacks narrative force. She’s living the resolution of ordinary daily conflicts and hopes, as we all are, but not living the arc of a story that draws her forward into a larger world.

Framing a goal as provisional is important because articulating it that way underscores that we can put away the goal entirely if and when there’s something more compelling to take its place. The lawyer worries about whether she should stay. Perhaps she shouldn’t. But she almost certainly should find the best way of staying, and pursue that provisionally up until the day she commits decisively to do a specific something else.

1. One provisional goal should be a story that can be pursued right now, a story that feels realistic to take action on more or less each day

So she takes out a sheet of paper. She writes a question, tentatively: “What would my twenty-eight year-old self, just graduated from law school, be proud to see me doing now, here at this firm?” And then writes two more questions: “What does the new firm really value? How can I do work that connects to that value, that earns me security?” The first question promotes introspection, the other pair promotes reflection on what matters in this firm’s specific corner of the world. The lawyer’s story, a provisional goal, should unite these strands.

Perhaps the story that emerges from this reflection is a story of “becoming”. For instance, the story might be about building a practice of my own at the heart of a larger firm. To use language I’ve explored in other posts about the 6 Cs of strategy, “build a practice of my own at the heart of a larger firm” represents a provisional commitment: something to pursue. Several concepts might then encapsulate the essence of how the commitment will be fulfilled. For our lawyer, these concepts would be things like:

- Build a critical mass of clients in a sector in which the acquiring firm wants to establish more depth

- Establish a handful of truly close, trust-based relationships with in-house lawyers in these clients, close enough that they could be the basis for a client relationship on the outside as well as on the inside

- Articulate several principles for what feels like good lawyering, and find a way to practice law consistently with those principles

- Learn how to meet people outside the firm’s current client base who might someday be clients, as a foundation for developing into more of a rainmaker and winning more autonomy that way

- Find one or two younger women in the acquiring firm to mentor, in a way that makes the experience count for something useful to others

Just like in strategy for a company, these concepts then guide specific operational choices. Some of these concepts may be straightforward to act on. In other areas, our lawyer might simply take a stance of patient readiness. She might not have a sense of whom she should mentor, but simply by articulating that finding the right mentees is an unmet aspiration, she’s created a catalyst for “seeing as.” For instance, if she starts working with a senior partner at the acquiring firm on some legal matter, she might now “see him as” someone who might be a bridge to finding one of these mentees.

This provisional goal of building a practice of my own at the heart of a larger firm has the capacity to direct focus and create energy. However, alone, this same goal may feel threatening, because it has the potential to bind our lawyer too closely to the path she’s on at her current firm, a path she very possibly should leave behind.

2. Another provisional goal should encompass the exploration that matters most

What makes our lawyer uncomfortable is that she just doesn’t know what else she wants to pursue. She doesn’t think she can afford to work for a non-profit. She doesn’t have the eminence to teach law. And she’s terribly busy. Every once in a while she reads something outside her field just for interest, or meets with someone who might beckon in an interesting direction, but she doesn’t have much time for these kinds of things and none of them actually seem all that helpful. She feels a flicker of interest here and there; nothing that pulls with sufficient specificity in any direction.

Our lawyer’s second story should address this gap head-on. It should be a story of discovering, a story of “finding”. With this in mind, perhaps she begins by thinking about questions like when she’s been most fulfilled, what she thinks about and reads about simply out of interest in the questions, what her greatest strengths are, what dreams she’s put aside, and so on. She writes down things that are worth discovering. Maybe some of the early entries on this list feel very general, too general to be useful to her – or they feel too specific, too micro. She writes: doing law for a REASON… how do businesses operate differently, more ethically… work for clients who BELIEVE IN SOMETHING… article I read recently on Richard Branson’s “B Team” – how to work in that spirit. Looking at what she’s written down, she tries to formulate a direction worth exploring. Not committing to, just committing to explore. Perhaps this gets to formulate as something like finding a way law can make a difference to more sustainable ways of doing business, and beginning to build perspectives, expertise and connections in that area.

With this “finding a way,” not knowing becomes the heart of a story, rather than what obscures the story. She sits down and makes a list of things to investigate. B Corporations. The law of cap and trade. How companies contract with their foreign suppliers in ways that promote good labor practices. The law of fair trade goods. What do lawyers at places like Tom’s and Ben and Jerry’s do differently? And so on. It’s a long list, perhaps. Too long to pursue in its entirety, at least at first. Which is fine. She does what an investigator on a television drama would do. She’s looking for clues. She starts somewhere. She keeps looking. She begins assembling the picture. And as she does, perhaps her story changes.

Living two stories looks like it is about adding things to do, but it is at least as much about focus, as subtraction. The two stories of building a practice and finding a way are demanding in their requirements. Commitment to them implies a way of editing down other commitments and achieving greater economy of effort in order to have the bandwidth – time, energy, presence of mind – required to move forward.

The lawyer’s stories have four qualities that make them likely to be good stories – and these are good touchstones to focus on in shaping one’s own stories:

- The story is expressive, in the sense of expressing deep, intrinsic commitments

- Living the story requires growth in understanding and capability

- The story is enabling, creating a foundation from which to pursue further, larger aims

- The story is at a time horizon that is long enough to open up new possibilities, but not so long as to be unreachable

With stories like these, we can move forward without the false limits inherent in the “trade-off view.” We can embrace both making the best of where we are and the search for different, even radically different options. Both of these become purposeful pursuits, advancing day-to-day and season-by-season. These stories become fulcrums to enable us to use our days to transform our lives.