The field of strategy has taken shape primarily in the context of large businesses. Entrepreneurs need strategy just as much as corporate CEOs do, but what they need from strategy is different.

In an earlier post, “What Does It Mean to Have a Clear Strategy?” I propose a definition of strategic clarity:

Commitment to a destination and to core concepts that shape the choices for how to get there

Illustrating this definition of strategic clarity with examples such as Nike and Southwest runs the risk of painting the wrong picture of what strategic clarity looks like in practice at an entrepreneurial company. Companies like Nike and Southwest have built finely-tuned systems to sustain an edge in specific ways to win in specific markets over the very long term. Start-ups, by their nature, represent vectors of exploration to find an answer to the classic strategy questions of where to play and how to win.

Three strategy fundamentals are parallel for both small, early stage companies and mature market leaders:

- Lack of clarity on commitments leads to churn as people at the organization pursue different goals, or as teams deploy savvy tactics in support of the wrong ends

- Enterprises of any stage and size need to make a lot of choices, and these choices will be most powerful if they fit together coherently, in a way that requires them to flow from a small number of core concepts

- Everyday work is most productive when people have a clear line of sight to choose what to do and how to do it based on an understanding of the bigger picture

We’ve all seen early-stage companies fall into traps from failing to learn these lessons. The founder who thinks she wants to keep as large an ownership stake as possible but whose actual commitment is to a substantive vision – and by extension to having investors who share that vision – ends up with slightly cheaper capital, but much less alignment. The founder who can’t describe a product vision in conceptual terms but who has strong opinions on every detail of the product ends up with a team who feel second-guessed on every detail and contribute very little to the advancement of the founder’s biggest ideas.

These parallels stand against a backdrop of immense differences. Large democracies and guerilla movements both need armed forces, after all, but need them in entirely different ways. Two main differences stand out:

- The central concepts in a mature company’s strategy together form a coherent answer to “how we win.” For an entrepreneurial company, the concepts will generally be a combination of core hypotheses about “how we win” and tenets about “how we explore” to find elements of a winning proposition that aren’t yet known.

- Strategy for mature companies is largely direct in the sense of focused on the production of value through exploiting an advantaged position in their target markets. Much of strategy for entrepreneurs is indirect: it is concerned with acquiring resources and building capabilities necessary to achieve future goals. This includes, centrally, the question of ensuring survival as the venture progresses. Take too much survival risk, in the wrong way, and the rest of strategy is irrelevant; take too little survival risk and one might well end up dithering, conservatively, while the window of opportunity slams shut.

These questions are dynamic. Entrepreneurial companies need to reexamine and revise their strategies much more frequently than mature companies, not only in the context of what we typically think of as “strategic considerations” such as evolving competitive landscapes, technology shifts and economic conditions, but also in the context of what can feel like tactical considerations relating to funding, hiring constraints, new customer opportunities and the like.

All these contrasts between what entrepreneurs and mature company CEOs need their strategy to do for them underscore a fundamental principle:

Entrepreneurial companies need tight focus on what is required to get to the next fundamental stage in their development – their strategies should reflect a progression through multiple, distinct eras toward their long-term goals.

It is almost definitional of entrepreneurship that the entrepreneur’s ultimate vision will be far, far beyond what is practical to act upon today. Nested one step underneath a bold vision, entrepreneurs need a visualization of how to evolve an enterprise through a series of eras, each of which has its own imperative and strategic logic, and paves the way to move into the era that follows. We often think of a set of eras as being like a ladder one climbs up, balancing on each rung while ascending toward the next.

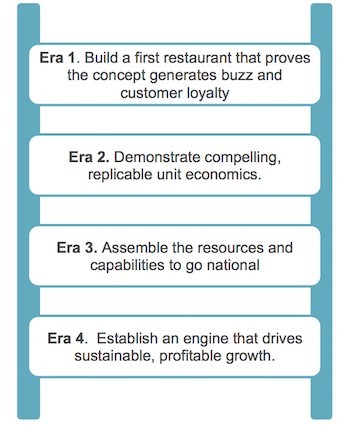

To give a concrete example, suppose an entrepreneur’s ultimate vision is to build a national chain based on a new restaurant concept. One can’t just do that. There’s a natural sequence that proceeds in something like the following way:

Each of these eras has its own natural imperatives, and its own logic for how the business needs to work. For instance, it isn’t necessarily a big deal to encounter an issue that compromises unit economics in Era 1 so long as the issue can be identified and solved, and so long as it doesn’t stand in the way of assembling the resources required to progress into Era 2. If, for example, the restaurant is too large, or the original staffing model is too heavy, those are the kinds of discoveries that can be acted upon easily enough in Era 2, if the underlying value proposition to customers is sufficiently compelling. The overhead burden could be quite high relative to revenue in Eras 2 and 3, so long as enough capital is available to fund rapid growth, but getting overhead in line and achieving net profitability is essential in Era 4.

An entrepreneurial enterprise progresses by “graduating” from one era to the next. Generally, there will be multiple factors that need to be realized together in order to “graduate” into the next era. For instance, in the restaurant chain example above, in order to progress to Era 2, something like the following set of milestones needs to have been achieved:

- The first restaurant is achieving distinctively strong customer results, which create confidence in the ability to successfully scale

- Operating results establish a strong basis for being able to project unit economics above a high threshold (e.g., sufficient profits at the restaurant level to achieve a 25%+ internal rate of return on the basis of a per-store build out cost at the level that one would expect to achieve once the chain scales)

- The business has raised enough capital to be able to build out at the least the next two units and to operate long enough to demonstrate the target unit economics and raise further capital for expansion

The details matter in specifying graduation criteria like these. For instance, does the company need to have raised the capital to build two more units and operate for 18 months in order to “graduate,” or does the company need a smaller amount of capital given good prospects of raising more as Era 2 proceeds? Is there a fourth criterion about the team that needs to have been built in order to turn the corner into Era 2, or can any talent gaps readily enough be solved as part of the work of Era 2?

Much of the art of strategy in building an entrepreneurial business is in specifying precisely what’s needed to graduate into the next era and then focusing relentlessly on those factors. If criteria are specified too ambitiously, beyond what’s really needed, that can hold back progress. For instance, our restaurant start-up can probably overspend on building out the second unit if it has enough capital, so long as it can paint a clear picture for future investors of how it will drive build out costs down as it scales. It could be quite a distraction at this stage to “value engineer” the build out too much, if much less time might be required to raise another couple hundred thousand dollars of seed capital.

However, it can be disastrous to miss “graduation criteria” that are essential. Let’s take the second criterion above: “operating results establish a strong basis for being able to project unit economics.” An entrepreneur with a sexy restaurant concept that customers love might well be able to raise the capital to build out a second and third unit without achieving this standard. But what happens then? She might get lucky, and the unit economics might fall into place. If they don’t, however, she’s unlikely to be able to get the kind of institutional capital required to graduate to Era 3. She could keep trying to raise angel money, staying in Era 2 longer and figuring out unit economics as she goes, but her burn rate is likely going up rather than going down as she expands. Time may well begin working against her in a much more challenging way than if she’d solved for the factors required to be more confident that she’d get the unit economics in the second “wave” of restaurants into the zone that future investors are likely to expect.

This example illustrates how the other two differences between strategy for entrepreneurs and strategy for more established corporations go hand-in-hand with the focus on progressing deliberately through a series of eras. Where strategic clarity for a more established company hinges on having a mutually reinforcing set of strategic concepts that shape the multitude of choices the company must make, for the entrepreneurial venture, there are likely to be a couple of strongly-held concepts and a parallel set of tenets for “how to explore” in order to drive toward answering critical unknowns and iteratively refining strategy. For our restaurant venture in Era 2, for instance, there might be clear concepts relating to the menu and how the staff delivers a distinctive in-store experience, but important unknowns about size, site location and the rent-traffic trade-off. Pretending that there’s clarity when there’s insufficient basis to be clear significantly raises the risk the venture will fail.

Better would be to design a clear “how to explore” into the strategy in Era 2. For instance, Era 2 could center around expanding from one restaurant to four, where each of the three new sites represents a rather different approach to question of restaurant size and site selection. In this context, “graduation” to Era 3 could involve proving out that one of these three models represents a scalable proposition, and using that demonstration to obtain the level of capital required to proceed. With this achieved the place served in the strategy by a tenet for how to explore in Era 2 gets translated into a more robust strategic concept about the site and physical build-out of the restaurant in Era 3. As this example shows, despite the big unknown, the team could be fully clear in Era 2 about what to do – but the what to do is shaped by work to answer a question, versus following from a proven strategic concept.

As this start-up grappling with restaurant size and site selection helps us see, maxims that are sensible enough for mature companies can easily lead entrepreneurial companies astray. Take something as innocuous as the principle to direct resources to where they will have greatest return. For the mature company, the return to be maximized is generally a direct return, which can be calculated in financial terms. For the entrepreneur, “greatest return” is often better understood in indirect terms: what will advance the venture best toward what’s required to graduate successfully into the next era. In some cases, this may be financially most advantageous, but these two goals will often diverge. Our restaurant entrepreneur financially sub-optimizes by trying different size and siting formulas for units two through four, rather than stamping out three units that reflect the formula she has most reason to believe will deliver performance. By varying the formula more, however, she raises the probability of having a clear demonstration that one of these formulas has the right economics to scale up. She may have less survival risk even at a higher burn rate, if she can raise capital on the basis of her successful units and lop off the bets that simply didn’t pan out.

An effective strategy for an entrepreneurial business is framed in terms of progression through a series of eras and achieves clarity about what to do equally from “known” strategic concepts and tenets of “how to explore” that systematize the resolution of critical unknowns. The fact that entrepreneurs need to revise their strategies more often, and less predictably, than leaders of more mature companies only raises the stakes for being clear and explicit about what constitutes the current strategy and what provides the basis for this strategy. Without this clarity, it is too easy in the heat of battle to revise strategy on the wrong level – whether reacting too “low down” (e.g., applying operational fixes when the overall financial model isn’t structured for success) or panicking and revising assumptions too “high up” (e.g., changing the destination when all that’s needed are some creative ideas for how to redirect and achieve “graduation” from the current era in an unanticipated way). The need for powerful, explicit strategy doesn’t imply that entrepreneurial ventures should engage in the kind of elaborate strategic planning processes that large companies generally do. In my experience, that’s rarely feasible or desirable. What entrepreneurs can do is make the mental space to articulate the current best understanding of strategy in an explicit way, to identify the weaknesses or gaps in this current view, and to create streams of action to address these areas at the same time that they proceed at full speed with the imperatives about which they’re most clear.

When we work with entrepreneurs, we almost always find that we can quickly reap a significant “clarity dividend.” Inevitably, founders and other leaders are spending a fair amount of time on non-essential questions – and not spending time on questions that are more important but where it is harder to figure just how to take action. The clarity dividend flows naturally from framing what is already known about strategy and making that explicit; paring back the activities that connect least closely to the critical path to graduating from the current era; and coming up with simple, practical ways to advance the critical path questions that have been obscured or neglected. This dividend almost always “funds” work on the questions that it previously didn’t seem there was time and space to address, enabling the small adjustments early that are so often the only substitute for big, costly, disruptive adjustments later.