Steve Reich wrote a fourteen-minute “speech melody” called Proverb. Five voices sing and refract a single line from Wittgenstein: How small a thought it takes to fill a whole life.

At one point last year, my father shared with me a poem from Jane Hirschfield, “The View from Here,” which begins:

Of the questions

we climbed with,

nothing survives.

Handholds, footholds,

juttings, cracks —

all roughness polished smooth.

In a correspondence that followed, he wrote about the way in which his own inquiry was evolving from trying to answer questions to figuring out the way that pursuit of certain questions had shaped a mind and a life.

Now the charge has become to live and go about reflecting differently, but this time to see more clearly than ever before where and when and how and why I arrived at all those places and encountered all those people and experienced all that “stuff” that my questions brought me to. Living the second time around is really a “first time” experience. I’ve never really done this before, ever.

As part of this inquiry, my father wrote to me one day that he’d been sitting in his study thinking about a teacher from his high school years, Mr. MacDonald. At that point in his life, my father was at his best deeply curious, and most of the time impatient with and unwilling to master school. Mr. MacDonald gave my father an essay to read by Abraham Flexner, the founding director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where Einstein spent his later years: The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge.

This essay is an ode to curiosity, exploring how “curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking…. It goes back to Galileo, Bacon and to Sir Isaac Newton, and it must be absolutely unhampered. Institutions of learning should be devoted to the cultivation of curiosity and the less they are deflected by considerations of immediacy of application, the more likely they are to contribute not only to human welfare but to the equally important satisfaction of intellectual interest.”

Flexner was himself quite a character. After graduating from Johns Hopkins at 19, back in the 1880s, Flexner returned to Kentucky, taught high school, and then founded his own college preparatory school embodying the idea of “no duties, only opportunities.” After pursuing and dropping out of graduate programs at two illustrious universities his thirties (as my father also did), Flexner became famous for a critique of American medical education. This led to an invitation to advise the heirs to the Bamberger department store fortune. Louis Bamberger and Caroline Bamberger Fuld wanted to start a medical school in Newark. Flexner enlisted them as the founding donors of The Institute for Advanced Study, which embodied the idea of “no duties, only opportunities” and provided an intellectual home for Einstein, John von Neumann and many others.

Throughout Flexner’s life, belief in the power of uninhibited curiosity possessed and animated him. He was like the man making lures in Jorie Graham’s poem “Reading Plato”:

Past death, past sight,

this is

his good idea, what drives

the silly days

together.

My father hadn’t thought about the essay for many, many years, and it was brought back to him by the combination of reflecting on Mr. MacDonald and reading my blog on Achieving Impact on a 1,000-Year Time Scale – itself a kind of exercise in “useless knowledge.”

He shared with me:

The reason why I found it so difficult to immediately identify the essay and its author has everything to do with the power of its influence on me. I remember reading it over and over as a revelatory experience. It became a self-consuming artifact that I absorbed entirely into my own thinking. It disappeared as it was and reappeared (in disguise) in the fabric of my being. Sixty years later, I had to tease it out of that fabric and piece it back into its original shape. To assimilate someone else’s thinking until it becomes your own and then to restore its true identity and full integrity is an ultimate act of appreciation.

Two weeks ago, we lost my father to a sudden heart attack.

He and my mother made “curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful” the daily current of our early lives. To my sister and I, curiosity never felt like an impulse one outgrows. Now, around every corner I turn, I see how the people and words and ideas my father found beautiful have “reappeared (in disguise) in the fabric of my being.”

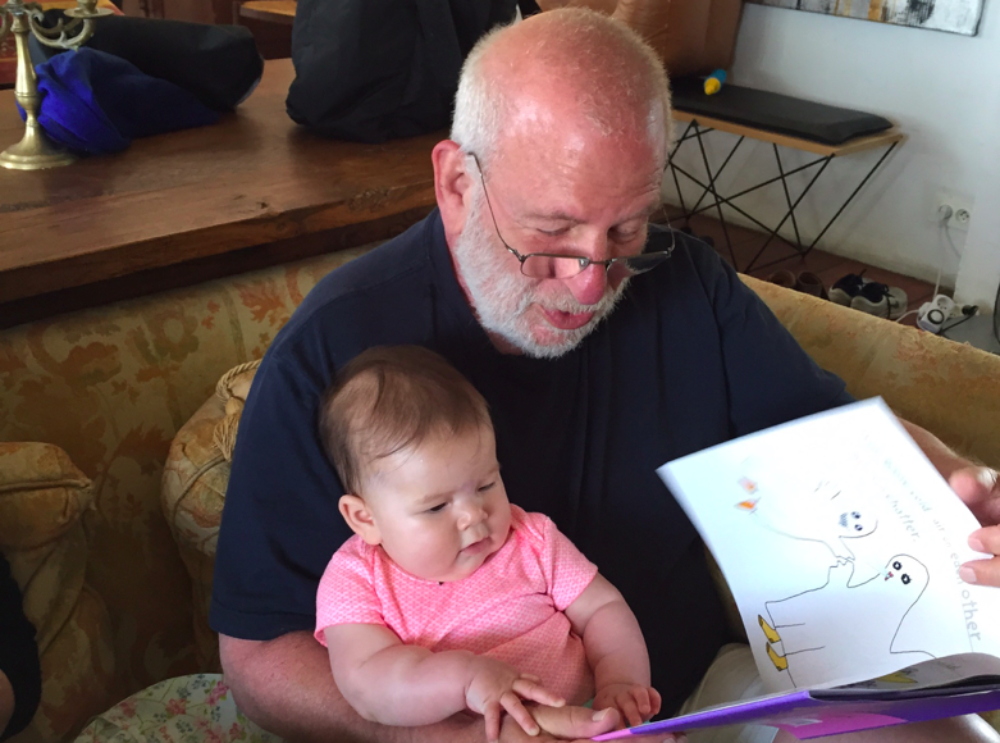

The picture I’ve shared here was taken in a farmhouse in Provence. We’d made the journey with our then five-month-old daughter Minh to celebrate my parents’ fiftieth anniversary. My father’s reading Minh her first favorite book, When Two Say Goodnight.

He’ll always be to us as he is here, reading with love, making each thought luminous and lasting, enough to fill a life.