At the core of our work at Incandescent is the question of how people and organizations achieve goals that are far beyond their grasp at the outset of their journey. From this perspective, an entrepreneur in her garage, a movement builder, and a chief executive committing to an imaginative leap regarding what her company could become are all engaged in the same human work.

Each has committed to a journey that calls to be undertaken as a whole quest, but can be advanced only in stages. This quest is impossible to fully visualize at the outset, such is its magnitude and its difficulty. Each era in the journey unlocks the conditions of the next. Approaching this journey calls for both reason and faith. Martin Luther King: “Take the first step in faith. You don’t have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.”[1]

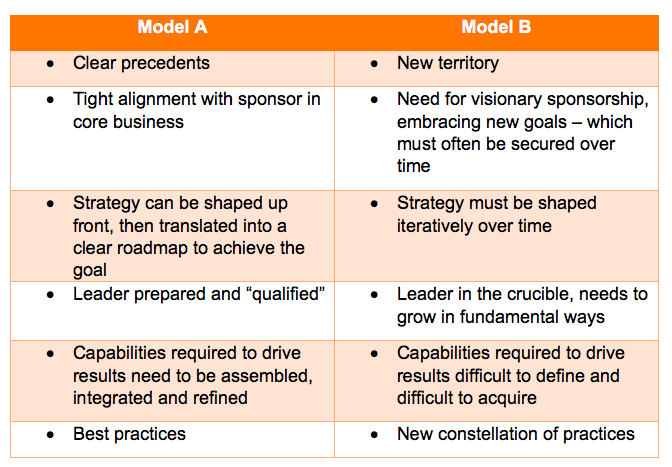

The logic of these journeys upends the logic of how most leaders in large enterprises drive results. Let’s be as precise as possible about how these logics differ.

The right-hand column logic isn’t better than the left. In fact, it is a highly illogical way to approach the problems of refinement and optimization that constitute most of the work most organizations need to do. The reverse is also true: the most dynamic growth companies are so geared to Model B that they find it difficult to value and execute the Model A work so critical to successful scaling.

Trying to undertake breakthrough innovation in large organizations is challenging because leaders have learned so well the disciplines of operating in Model A, that it is difficult to unlearn these in order to acquire the new disciplines critical to Model B. We see this disconnect near the beginning of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass:

And here I wish I could tell you half the things Alice used to say, beginning with her favorite phrase “Let’s pretend. She had had quite a long argument with her sister only the day before – all because Alice had begun with “Let’s pretend we’re kings and queens;” and her sister, who liked being very exact, had argued that they couldn’t, because there were only two of them, and Alice had been reduced at last to say, “Well, you can be one of them then, and I’ll be all the rest.”

Model B talks past Model A in large organizations. It isn’t that top leaders find it difficult to say “let’s pretend” – not only do they say that all the time at offsites, they commit real capital to innovation with a clear up-front understanding that it’s essential to approach these efforts like Alice rather than like her exact and exacting older sister. What’s difficult is to stay in the Alice space for the length of the journey, and to turn Alice’s Model B into disciplines that are in their own way at least as demanding as Model A.

Model B journeys demand attention to strategy – what is the shape of the climb toward one’s ultimate vision – even as they defy planning. Strategy as a working picture of the long climb orients the individual, and gives coherence and focus to the “we” that must come together for any large undertaking to advance. But conceptualizing the path to climb is the least of the work. The cliff face at hand often seems impassable. Upward progress stalls until one gets unstuck, finding some way to overcome the challenges of this particular point in the ascent. The disciplines of Model A ensure that execution never gets stuck. The disciplines of Model B confront the inevitability of getting stuck, and aim to avoid the trap of solving the problem one knows how to solve, rather than the real, harder problem underneath.

The climber who begins a journey through the looking glass is never capable of completing it at the outset. She is transformed through the journey; her inner work mirrors and fuels the outer climb. What is required of me? How do I become a more perfect instrument of the end I’ve committed to pursue?

Much of what I write about in On Human Enterprise falls under the heading of disciplines of Model B: for instance, the discipline of integrating the visionary optimism of “let’s pretend” with the clinical, skeptical realism necessary to build a bridge from present limits to the visionary goal, which we at Incandescent call the “duck-rabbit balance.” The world beyond the looking glass does make sense; it simply demands that we take off the reading glasses of Model A and put on a new set of spectacles.

[1]

King's words as remembered by Marian Wright Edelman, who has described listening to his speeches at Spelman College.