One of the things long friendships teach us is that one needn’t say everything at once. Old friends are beautiful to us partly because we can linger on each facet of them, seeing each part in light of the whole and knowing that the rest will be there to return to.

Each time I read one of the reports that my friend Dov Seidman develops—each one a formidable march into the heart of the big questions of moral leadership—I can hear his voice, and experience the feeling of being intimately in conversation. Just as if this letter were one encounter in our decades-long dialogue, I’d like to explore here a single facet of the multi-dimensional response that work like Dov’s deserves—but a facet right at the heart of On Human Enterprise.

In the latest HOW Institute for Society report on The State of Moral Leadership in Business, Dov writes in his opening letter:

In times of such crisis, people naturally look to authority—to those in charge—for honest answers, principled decisions, and courageous actions. They look to leaders for hope—and hope can only be fostered by leaders who bring out the best in people, who inspire collaboration, a common purpose, and future possibilities.

Unfortunately, many business leaders seem overwhelmed by employees’ and stakeholders’ demands for clear public statements on social and political issues, regardless of whether these issues impact them personally. In the current Zeitgeist, the term “moral confusion” has emerged as a catch-all term to describe a critical leadership challenge: The need for CEOs and other leaders to rely on strong moral frameworks that can inform the issues which they engage, empower them to engage in a manner that all stakeholders understand, and give them the tools to do so at scale, over the long term.

The single greatest leadership challenge of the 21st century is, therefore, to nurture and develop moral leaders who lead with moral authority and ensure that leaders, and only these leaders, occupy positions of formal authority at every level, sector, and dimension of society

What’s important and distinctive about the HOW Institute’s work is the specificity with which they flesh out concretely what “strong moral frameworks” mean in practical terms, providing an operational definition that flows from a set of seven practices, each of which yields tangible behavioral litmus tests. The practice of “See Humanity in Everyone,” for instance, connects to specific behaviors regarding the language leaders use, the nature of the relationships they build, and the way they listen. Whether and how leaders apologize – a profound behavioral window into a leader’s moral framework – is one of the litmus tests for the practice of “Demonstrate Humility.”

Building on these operational, measurable criteria, the report goes on to lay out page after page of data, establishing the pervasive demand for moral leadership; the scarce supply of moral leadership as measured by direct experience of a set of key behaviors; and the difference that moral leadership makes to a range of factors that shape effectiveness at work. The data on this last point is striking. It isn’t surprising that 70% of people who identify their managers as demonstrating a set of behaviors that put them in the top tier of moral leadership attest, “People on my team take full responsibility for their actions and do not hide from their mistakes” versus only 25% who experience that when they work under leaders in the third of five tiers of moral leadership. But we see the same divergence on questions that seem, on their face, to be less directly connected to ethical fiber. For instance, “people on my team know the key responsibilities and priorities of their roles” (79% vs. 39%) and “people on my team experiment and try new ideas” (66% vs. 28%).

To ask a very basic question: why should this be true? Why isn’t something as basic as knowing key responsibilities and priorities simply a matter of managerial effectiveness, largely uncorrelated with something as lofty as moral leadership?

To answer this question, I'd like to start with what on the surface may feel like an unrelated observation: the ubiquity in business of empty words.

Open any PowerPoint and you’ll see what seem like bold commitments, stated in abstract terms: winning, delighting customers, becoming an employer of choice, seamlessly integrating systems…

In 2016, I wrote an article for Talent Quarterly titled “Leaders Get the Culture They Deserve: How to Deserve Better.” The piece began:

I’ve come to regard them—CEOs intoning earnestly about their “future state” cultures and the HR heads who are all too often the primary agents of trying to arrive there—the way a psychiatrist might regard a never-married, wealthy, attractive 48-year-old, seeking matrimony without changing too much the life that he’s grown used to. Big companies are giant production functions, and part of what they’ve evolved to produce is the cultures they have today. Reality is complicated, but a useful simplification for a CEO is to begin with the assumption that top management, a group of which he or she has generally been a part for several years, has produced the culture it deserves.

Most leaders look at how their company (or their unit, or their team…) operates, and how their company performs and want things to be better. The very next thing they do is to say some words about how they think things should go. And that’s where the trouble begins.

To stay with the example of trying to shape culture and quote further from my argument in TQ:

Most work on culture begins from a small number of agreed-upon values or cultural imperatives, then tries to move an organization to align with these ideals broadly, across the many specific contexts in which people work. Accountability, speed, innovation or any handful of touchstone words like this are meant to crystallize a complex web of actions that together make a company tight, fast or successful in generating and capitalizing on new ideas. This seems sensible, perhaps because companies with distinctively effective cultures do often use touchstone words, and employees across a broad range of contexts act in alignment with these words. For instance, Zappos talks about Delivering Happiness, and has also created a vivid sense of what it means to be a place where employees “create fun and a little weirdness” in service of that goal. Similarly, any Southwest team member can riff at length about what “warrior spirit,” “servant’s heart” and “fun-luving attitude” mean to them and mean in practice.

Unfortunately, it is almost never the case that the real patterns of how people act, think, and feel take shape in this way. Almost no one derives what to do in the concrete rough and tumble of everyday life from a few touchstone words. In companies like Zappos and Southwest, these powerful words are condensations of patterns that are already durably embedded. This doesn’t mean that the words don’t matter. They help people internalize how the many things they observe and experience are in fact manifestations of the same big idea, which strengthens the intellectual and emotional reinforcement of these examples. The flight attendant humorously improvising or the pilot pitching in to tidy up the plane aren’t “just things those people did”: they’re distinctive behaviors that they do routinely because they are committed to being cheap and being fun. However, when these patterns aren’t already there, using a word like “cheap” or “fun” is like pushing on a string.

The problem with management, as one encounters it at every level, from the boardroom to the shop floor, is how rare and difficult it is for any of us to demonstrate passionate, complete, relentless commitment to meaning what we say.

What it feels useful to say as a manager is generally some expression of commitment to making things different and better than they already are. But as soon as those words have left our mouths, they create an inconsistency, a tension, a demand. It is a tremendous burden to feel, having spoken, that we are then irretrievably committed to wrestle reality into conformance with our words. But the alternative is to live with falsehood.

The path of wisdom isn’t to refrain from setting high standards or from voicing them. Rather, it’s to spend our waking hours in constant dialogue with the gaps high standards open up.

The secret of management is meaning what we say. And the secret of meaning what we say is to recognize that most of the time we aren’t yet meaning it enough—and that, therefore, there’s work to do to get closer, at the nitty-gritty level of what-I-do-next, to what we meant.

This is true when we speak about matters of wide concern in the language of ethical principles:

OpenAI acknowledges the importance of balancing innovation with ethical considerations. The organization is committed to advancing AI technologies for the benefit of society while actively working to avoid potential negative consequences and ensuring the responsible development of AGI.

And it is equally true when we speak about matters of narrow concern, with everyday words, as when a manager says: “you will be responsible for goal X, and you will be empowered to make the decisions required to achieve this goal.”

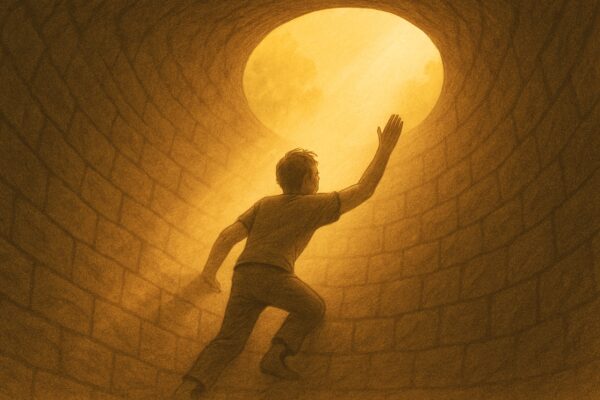

To return to Dov and the Moral Leadership report, at the top of page 21 are the simple words: “Moral leaders take the time and make the space to pause.”

The report explains how a pause enables us to reflect, and, in that space of reflection, to reconnect with “our sense of purpose and the values and relationships we care most about”—or, in the simpler terms I’m using here, to remember what we meant. The pause gives us space to rethink and experience the contrast between what we meant and where we are, and what we’re doing now. And the pause gives us space to reimagine what we might do next.

Dov loves to quote Viktor Frankl:

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Effective individuals in every field of endeavor go further than their peers in meaning what they say. Elemental as that is, it is an incredibly demanding and powerfully differentiating standard.

Moral leaders, knowing the power of meaning what they say, simply step a little further back—and from that higher ground, ask what’s most worth saying and most worth meaning.